As soon as he drew it on the napkin I knew I had to grab it. My worst fear was that someone was going to sploosh ketchup or jambalaya on it, and then it would look like a crime scene photo.

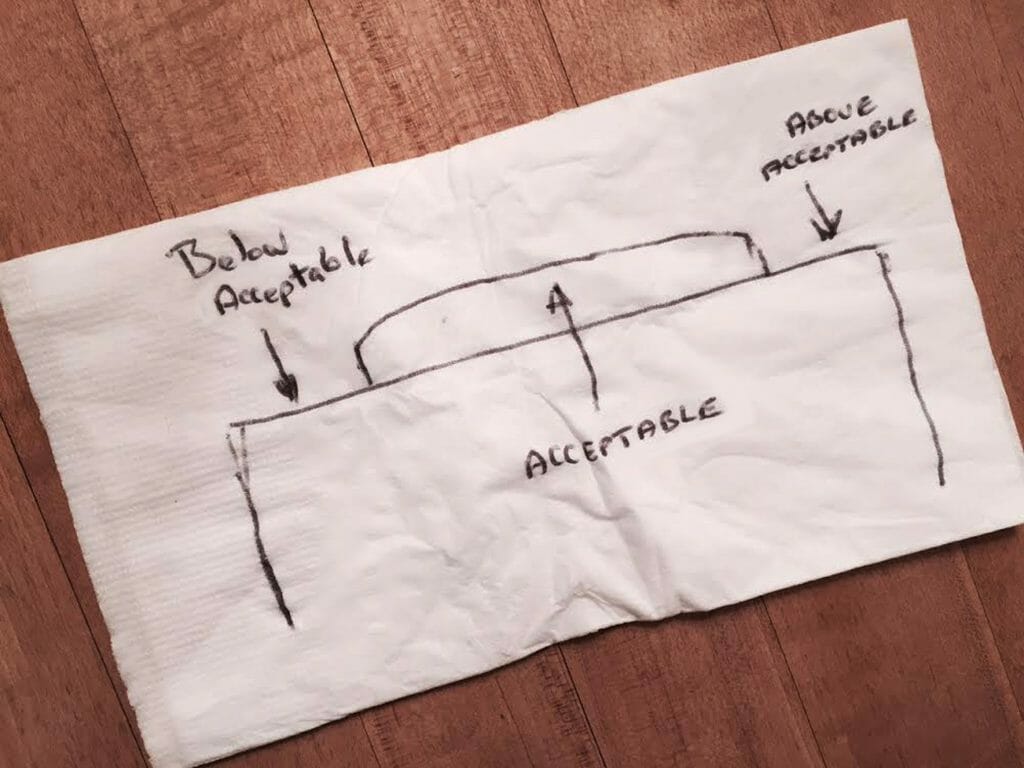

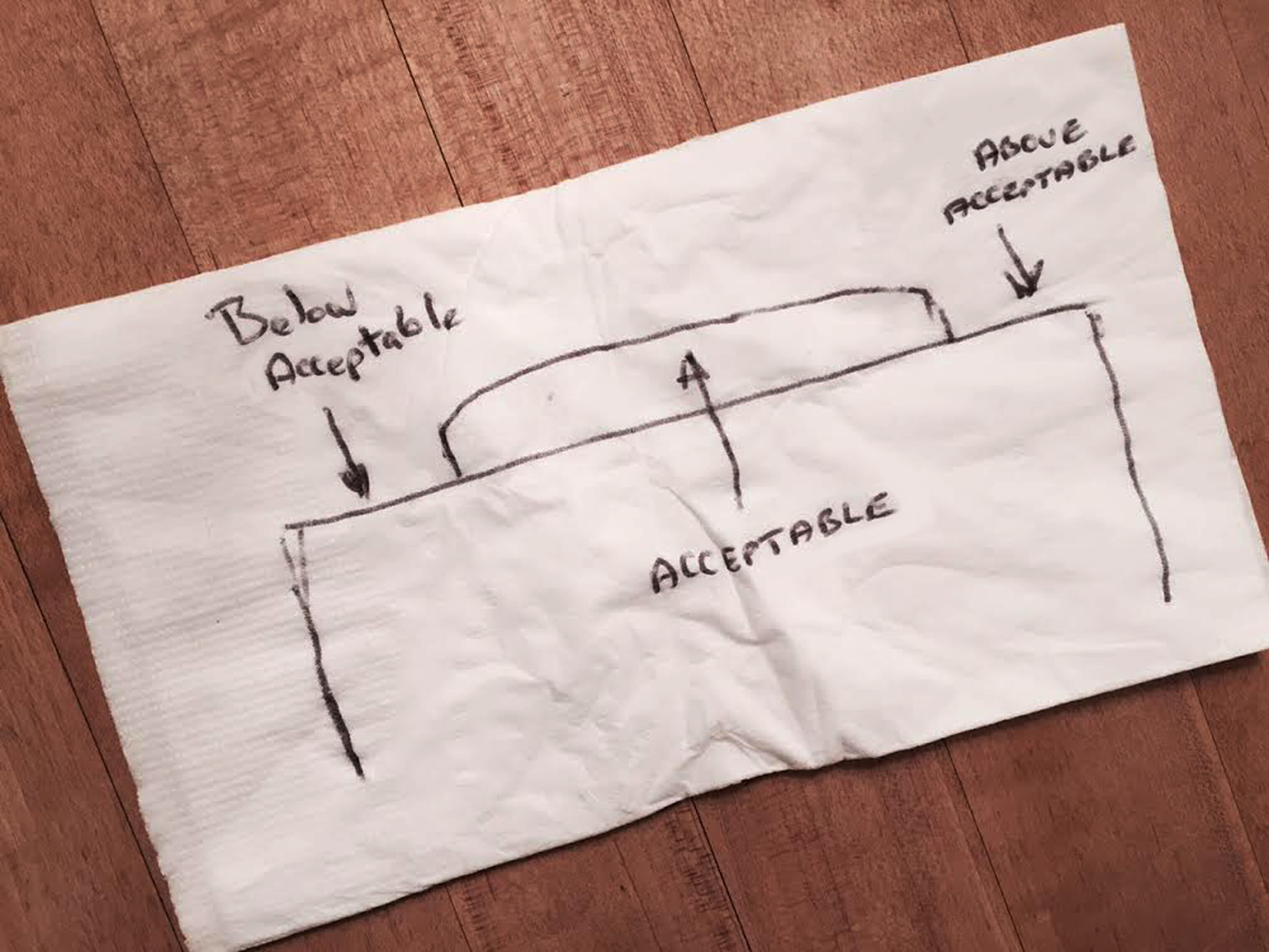

I’m talking about the hand-drawn graph in the photo for this article of course. It was sketched at a restaurant dinner table by none other than the golden voiced Aussie, Peter Walsh, President of NazDar SourceOne. While his drawing skills may be somewhat limited compared to others in the industry, the emphasis and meaning on what he was illustrating are exceptional.

The basic nugget of our conversation was centered on the effort and financial expense shops go through on their continuous improvement journey and the impact that has with their customers. What’s the divide between final production results for what is Not Acceptable to Acceptable to Above Acceptable?

Why were we talking about this stuff instead of sports or families or movies or any other normal dialogue that people might share at a restaurant? Because that’s what anyone in this industry does over dinner and a few beers. C’mon!

Think about how your shop fits in. I’m curious to see what you think too, so please leave some comments!

For any decorated apparel shop across the land, as they continue to expand their business their skill and expertise grows as well. Every step from starting an order to finishing an order comes under scrutiny at one time or another, and steps are taken to improve it along the way. That’s completely natural and most certainly warranted. We all want to get better. (Some people actually work at it too.)

But what’s interesting is the shops that go above and beyond what anyone else is doing.

Sure their thinking and effort paves the way for a lot of great things to happen, but at the end of the day are they a more profitable company? Is the dedication to obtaining complete perfection, and delivering results way beyond what the customer requests on the order, worth it?

What the customer deems acceptable is the bulls-eye we’re shooting for after all.

They are the ones ultimately that decides if the techniques we use in production make sense with their shopping dollars. Either they will buy the shirt or they won’t. Either they will continue to use us as a vendor or they won’t.

I’m sure we have all lost customers because someone else was a nickel cheaper. Did it really matter that there’s something “extra” in the print just because you are more craftsmanship oriented than the next shop? Doesn’t that just burn you up inside?

In today’s commodity oriented, everything driven by price, online world, when is over-reaching expectations grasping at straws? At what point is it just too much?

There’s a point of diminishing return somewhere in any process where if you keep loading in more improvements to a process, but the requirements in time or money to back the improvements might strip the potential profit away from the job. Improving anything has to make sense to each shop’s situation.

On the other hand, over-delivering on value is the best way to obtain more clients by simple word of mouth. If someone only expects X, and you deliver X + Y. You become unique.

So the presented question is this: Are the results for those shops that strive for the Above Acceptable route worth the extra effort and money invested to get to that level? If it doesn’t make you any more money, should you do it?

If someone is only willing to pay for a Happy Meal, offering them a Filet Mignon may strike some as unwarranted. Hell, the customer may even say “I didn’t order this?!”

Delivering the Happy Meal as ordered might be more profitable. But on the other hand, if you can offer Filet Mignon to people expecting a Happy Meal, and you’ve built an infrastructure that allows that to be more profitable than other shops who can only serve what’s expected…then you’ve got something. Getting to that point is the trick.

Vince Lombardi famously said, “Perfection is not attainable, but if we chase perfection we can catch excellence”.

But can you have excellence without all the fancy gear?

I’m positive there are fantastic printers out there that don’t use computer to screen imaging, LED’s for exposure, roller frames, an automatic press, bar-coded work orders, or even the latest bit of printing technology. I’ll bet there’s a craftsman out there somewhere that is still pulling a squeegee on wooden frames, just because that’s the way they’ve always done it and they are masters of that skill. There is nothing wrong with that if it works for you.

Usually when shops upgrade their equipment it is not just for the ability to produce better prints. More often than not, it’s about saving labor dollars, time on the production schedule, energy or other consumables. With better toys in the shop to play with, most companies can produce better prints as well.

That’s because a machine is going to be more consistent than a person. I don’t care how great you are at pulling a scoop-coater for screens, an auto-coater is going to give you better results every time. It is consistency we crave in this business. Not to mention you can lock in your frames and walk away and do something else, essentially doubling your efficiency.

Do you need an auto-coater? No, you can do the job by hand…but if you have fifty of them to do before the next shift, it sure is nice to be able to coat them two at a time while you are working on other tasks simultaneously.

The more you standardize the work, the more consistent your results will become.

At the end of the day, everything involved with producing the order determines if you are a success or not. Consider your shop’s volume and the tasks involved in production. Are there techniques or equipment available to make it easier, or to increase your production rate, or to lower your consumable or labor costs? You bet. When is the last time you did an ROI study on something that could potentially improve one factor in your shop? Most shops are just so consumed with getting all of the orders to ship on time, that the mental strategy of getting to the next level is constantly put off. Perfection becomes procrastination.

On Peter’s graph there are three sections. The chunk that is deemed Acceptable is the largest. With Not Acceptable and Above Acceptable flanking the ends of the graph. Where does your shop fit on the graph with most of the work that you churn out?

If you aren’t getting any more money for whatever you do that’s beyond what’s expected…would you still do it? Have you ever added up all the “extras” you provide to see what that really costs per order? How can you deliver Above Acceptable work, but have the same (or better) margins as shops that slug away with production that is just Acceptable?

As professionals, our constant aim is to deliver value and create trust with our clients. This keeps them coming back for more. Competition is fierce, and it seems lately that it’s only going to get uglier. The point of this article is just to throw you the idea that examining “why” you are doing something is a good thing.

There’s no right or wrong answer here. It is you that determines the value and the comfortableness of the profit margin after all. I’d love to get your shop’s take on this answer.

In the comments section, share your thoughts on the subject! What do you do?

20 comments

tommystsf

Marshall

This is great article. I’ve been printing since 1987, with much focus on contract work (my previous company was Target Graphics), which brings down the added value to profitability ratio to extreme lows. Yet, I have had much success promoting Exceptional service and quality to resellers. This includes 4color process on darks (25 SGIA Awards) and overnighting product at our expense if we are delayed in production. Anything to provide a superior print on time with a smile.

That said, it was a tough road. We have to charge more than many contractors to support this. It required enormous marketing efforts and communication to won folks over.

Futhermore, efforts were made to offset higher labor an material costs with effecient operations so that pricing remained fair and profits high.

Yet in all the years I have done this, I never quite asked myself the question you posed “is it worth it”. I just trudged foward with an idea, massive R&D, massive attention to setting up systems and training. It worked, but I was much younger then.

In 2015, I will ask myself that question more frequently. Now days are tougher than ever and public perception of value vs cost are more disconnected than ever.

On a final note, as tshirts have become a cheaper commodity, I believe it is more necessary than ever to set yourself apart. But as your article highlites, the added value margin has shrunk.

Perhaps it’s a matter of providing a Cadillac for a Chevy price rather than a Porsche, all while maintaining a cost only slightly higher than a Chevy.

Thanks for turning my gears.

Tom Vann

atkinsontshirt

Awesome comment!! Thank you so much for taking the time to write.

Peter Walsh

Marshall, Thanks for the great company the other night, and for converting my ramblings into an intelligent business question.

Garment decorators face the choice between doing what is acceptable and going the “extra mile” every day. Sometimes I understand it, and other times I don’t. Screen tension is a common example. With care and attention a shop can stretch their Retensionable frames up above 40 – 50N. We all know that printing at higher tensions allow faster print speeds and improved print quality, which raises the question; “Why don’t all print-shops stretch their frames to print at Max Tension?” The answer is because it takes more work to stretch the frames to these higher tensions, and the mesh is more susceptible to rip from routine handling out on the print floor.

I was in a successful garment screen-printer the other day, and if you can believe it they were using stretch and glue frames with mesh tension below 30N. I expect that if you were to look at one of their prints under a loupe, and compared it to the same print produced at 50N, the image produced at the higher tension would be just a little bit crisper and cleaner. The problem in this example is that the average consumer doesn’t look at a printed garment under a loupe, and they won’t assign an added value to the marginally higher print quality.

Another interesting fact about the shop with the stretch and glue frames is they use permanent block-out, and a bead of caulk inside the frame to seal the mesh. This approach allows them to print without using any tape on the inside or outside of their frames. The major benefits of this tapeless approach are that it saves the company a boatload of money in labor and materials when preparing and reclaiming screens, while greatly reducing their environmental impact. All of which result in lower production costs, increased profitability, and a more successful company.

atkinsontshirt

Awesome comment Peter!! This is exactly what I meant in the article.